Transfusion medicine

Transfusion medicine handbook

The Transfusion Medicine Handbook is designed to assist hospital staff and other health professionals in modern Transfusion Medicine Practice.

6. Special Circumstances

6.14 Haemolytic Disease of the Fetus and Newborn (HDFN)

HDFN occurs when maternal IgG antibodies (most commonly anti-D) travel across the placenta and bind to fetal red cells having the corresponding antigen. The affected fetal red cells may be destroyed and lead to fetal anaemia.

The antibodies that cause HDFN are produced either from previous transfusions or pregnancies (when fetal red cells with paternally derived antigens that the mother lacks, enter the maternal circulation).

In the most severe cases of HDFN the fetus may die in utero or be born with severe anaemia that requires exchange transfusion. There may also be severe neurological damage (kernicterus) because of a high bilirubin level.

Anti-D, an antibody to the RhD antigen, is the most important cause of HDFN. Clinically significant IgG antibodies against other blood group antigens can also be responsible for causing HDFN for example anti-c, -K, -E, -Fya. These antibodies occur in about 0.5% of pregnancies and may occasionally cause severe haemolysis. Although ABO incompatibility between mother and fetus is common, severe HDFN due to IgG anti-A and anti-B antibodies is very rare in New Zealand.

Screening in Pregnancy

All pregnant women should have the following antenatal testing performed:

- An ABO/RhD type and red cell antibody screen as early as possible during each pregnancy, preferably at the first prenatal visit (typically 8–12 weeks gestation) or early in the first trimester

- All women irrespective of RhD type should also have an ABO/RhD type and red cell antibody screen performed at 28 weeks. For RhD negative women, the specimen should be collected before giving prophylactic RhD immunoglobulin

- When a red cell antibody is detected, its specificity must be identified, clinical significance determined and risk of HDFN assessed. If the antibody is clinically significant, the level should be measured by titration or quantitation [11].

- If a significant maternal antibody is found it may be useful to test the father's red cells to see if they carry the antigen against which the antibody is directed. If homozygous for the antigen concerned, the fetus will also be positive. If heterozygous, there is a 50% chance that the fetus will be positive.

- Fetal RhD genotyping using non-invasive prenatal testing may be considered for high risk pregnancies according to local guidelines.

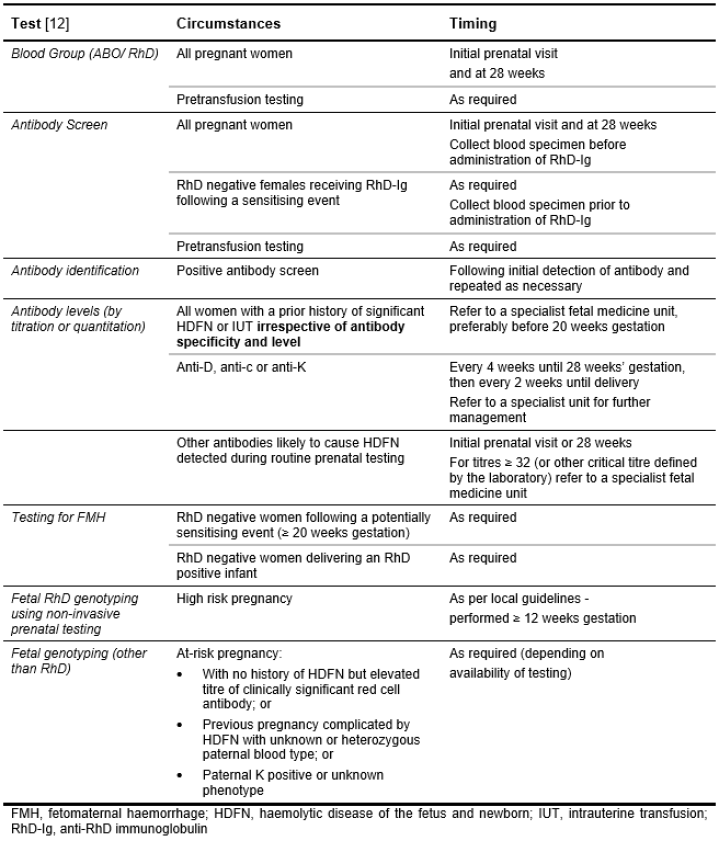

- ANZSBT provides guidance on the timing of tests, see Table 6.10: Routine prenatal testing [12].

Table 6.10: Routine Prenatal Testing

Management of HDFN

It is important that women with potentially severe HDFN are referred without delay to a specialist fetal medicine unit. The referral should be made prior to 20 weeks in those patients who have had a previously affected baby. Management of an affected fetus may include intrauterine transfusion, early delivery, phototherapy and exchange transfusion.

Prevention of HDFN Due to Anti-D

The minimum volume of RhD positive red cells that will immunise a RhD negative woman is of the order of 0.1 - 0.25 mL. The administration of anti-D immunoglobulin to an RhD negative mother within 72 hours of the birth of an RhD positive infant reduces the incidence of Rh isoimmunisation from 12 - 13% to 1 - 2%. A small number (1.5 - 1.8%) of RhD negative mothers are immunised by their RhD positive fetus despite postpartum administration of anti-D immunoglobulin. This number can be reduced to < 1.0% by routine antenatal prophylaxis with anti-D immunoglobulin at 28 and 34 weeks of pregnancy.

Anti-D immunoglobulin should not be given to RhD negative women with detectable anti-D except where the antibody is passively acquired due to prior antenatal administration. If unsure whether the anti-D detected in the mother’s blood is passively acquired or preformed, the treating clinician and/or a NZBS Transfusion Medicine Specialist should be consulted. If there is continuing doubt, anti-D immunoglobulin should be administered. Although there is no benefit in administering anti-D immunoglobulin to a woman who is already sensitised to RhD antigen, there is no more risk than when it is given to a woman who is not sensitised.

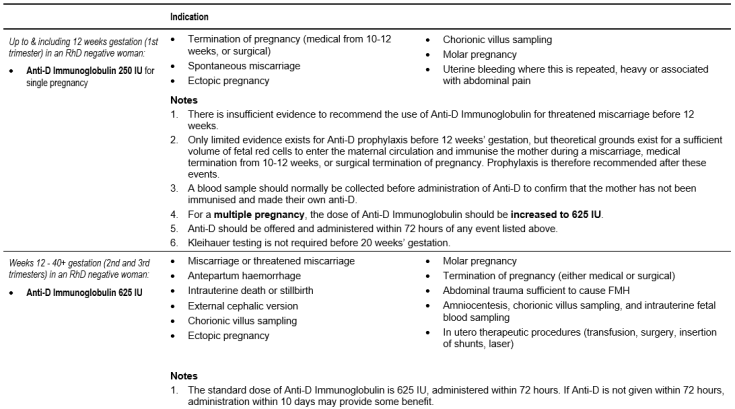

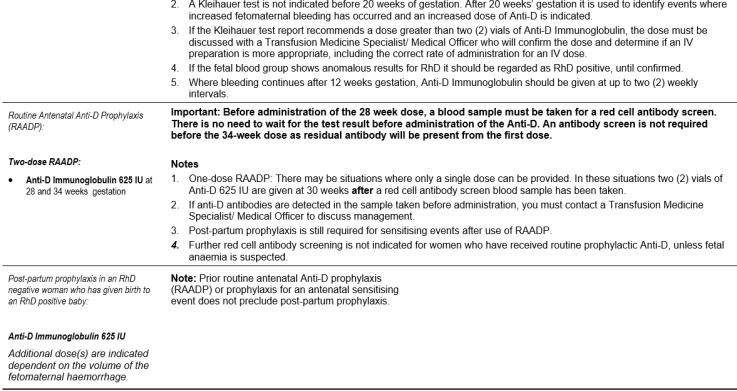

Current NZBS guidance on use of anti-D is summarized in Table 6.11: Dose and Indications for the Use of Anti-D Immunoglobulin. This is derived publications as well as discussion within the NZBS clinical group [13] [14] [15]. It should be noted that the NZ Ministry of Health does not currently recommend routine antenatal anti-D prophylaxis (RAADP).

Table 6.11: Dose and Indications for the Use of Anti-D Immunoglobulin

Laboratory Assessment of Fetomaternal Haemorrhage (FMH)

- The Kleihauer acid elution test is widely used and can detect haemorrhage of 0.1 mL or less. False results can occur and the test is less reliable in the first two trimesters of pregnancy when there is an increase in the level of fetal haemoglobin in the maternal red blood cells. Clinicians using this test should be aware of these limitations. The Kleihauer test is used to determine if additional Anti-D immunoglobulin is required. Therefore, the standard dose of Anti-D immunoglobulin should still be administered if a negative Kleihauer test is obtained.

- There is no need to assess the size of FMH prior to 20 weeks gestation as the standard 250 IU (< 12 weeks) and 625 IU (12 - 20 weeks) doses of anti-D immunoglobulin will cover the maximum likely FMH.

- It is recommended to assess the size of FMH after 20 weeks gestation. A blood sample should be taken from the mother as soon as possible after the potentially sensitising event and before the dose of anti-D immunoglobulin is given.

- Results reporting the fetal bleed in mL of red cells should be promptly available so that anti-D immunoglobulin can be given within 72 hours of the FMH.

- For large bleeds greater than 4 mL, repeat testing should be performed at 48 hours following each intravenous dose of anti-D or 72 hours following each intramuscular dose of anti-D immunoglobulin to check for clearance of fetal red cells and, if still positive, additional dose(s) given.

- Flow cytometry, a more accurate and reproducible method for measuring FMH, is not yet widely available. It is currently only indicated for FMH larger than 2-2.5 mL.

Timing, Dose and Route of Anti-D Immunoglobulin

- Anti-D immunoglobulin prophylaxis should be given as soon as possible and always within 72 hours of a potentially sensitising event.

- If anti-D immunoglobulin has not been offered within 72 hours, a dose given within 10 days may provide some protection.

- A 625 IU dose of anti-D immunoglobulin will protect against a FMH of up to 6 mL of RhD positive red cells (equivalent to 12 mL of blood). Where testing shows that a FMH of greater than 6 mL has occurred, additional dose(s) of anti-D immunoglobulin must be administered. In this situation, the recommended minimum dose is 100 IU per mL RhD positive red cells.

- Where more than 1250 IU of anti-D immunoglobulin (two 625 IU vials of Rh(D) Immunoglobulin-VF) is indicated, consultation with a NZBS Transfusion Medicine Specialist/ Medical Officer is recommended.

- For FMH requiring a large anti-D immunoglobulin dose, the maximum recommended administration rate is 3000 IU every 8 hours to reduce the risk of an adverse reaction arising from rapid clearance of fetal RhD positive red cells. As it is recommended that no more than 4 mL is injected intramuscularly at each site, Rhophylac, an anti-D immunoglobulin product suitable for intravenous administration, may be an appropriate alternative. Note that women receiving such large doses frequently have febrile reactions as the RhD positive red cells are haemolysed by the Anti-D Immunoglobulin.

- Recipients who have a moderate or severe thrombocytopenia should not receive intramuscular injections. The standard anti-D immunoglobulin provided by NZBS, Rh(D) Immunoglobulin-VF, is suitable for intramuscular use only. It may be given by intramuscular or subcutaneous route; it must not be given intravenously. Rhophylac, an anti-D immunoglobulin product suitable for intravenous administration is held at NZBS sites and can be obtained following consultation with a NZBS Transfusion Medicine Specialist/ Medical Officer.

Whilst there is some evidence to suggest that intramuscular administration of Anti-D Immunoglobulin may be associated with an increased risk of lack of effect in patients with a BMI >30, there is currently insufficient evidence to support a change to clinical and laboratory practice at the present time. A Consensus Statement recommended that for women with a BMI ≥30, particular consideration should be given to factors which may impact on the adequacy of the injection, including site of administration and the length of the needle used [15].The following is recommended where a woman has received an appropriate dose of anti-D immunoglobulin followed by a further risk event for immunisation.

- Where the previous dose was given 2 or more weeks before, a further dose(s) of anti-D immunoglobulin should be offered.

- Where the previous dose was given less than 2 weeks before, a further dose of anti-D immunoglobulin should be offered where the pregnancy is more than 20 weeks gestation. Where testing indicates a FMH greater than 6 mL, additional dose(s) of anti-D immunoglobulin must be administered.

- Where there is continual uterine bleeding that is judged clinically to represent the same risk event, further dose(s) of anti-D immunoglobulin should be offered at a minimum of 6 weekly intervals. In pregnancies > 20 weeks gestation, estimation of FMH should be undertaken at 2 weekly intervals and the presence of fetal cells should prompt an additional anti-D immunoglobulin dose to cover the volume of FMH.

Further observations and comment on the guidelines for the use of anti-D immunoglobulin are available in the NZBS Clinical Compendium.

Non-invasive Fetal Genotyping

A maternal blood sample may be used for non-invasive testing of cell-free fetal DNA to predict the fetal red cell phenotype. This has particular value in identifying a fetus that is unlikely to be at risk of HDFN. In the case of a sensitised RhD negative woman, the absence of the RHD gene predicts for an RhD negative fetus. As such, aggressive monitoring of the mother’s anti-D titre and the health of the fetus is unnecessary. Fetal RhD status is also useful in determining whether anti-D immunoglobulin prophylaxis is required. Rarely, such as when genetic changes lead to gene silencing rather than deletion, genotype determination does not correlate with the antigen expression on the fetal red cells.

Certain criteria need to be met before obtaining fetal DNA for genotyping; the mother’s serum contains an IgG antibody of potential clinical significance and the father is, or may be, heterozygous for the gene encoding the antigen of interest. Fetal genotyping for RHD, C, c, E and Kell is available for suitable patients. A NZBS Transfusion Medicine Specialist can be consulted on whether it is appropriate to refer samples for testing.